NEPAL: April 2004

Nepal is a country that held many surprises for me. Most of my preconceptions

about the kingdom turned out to be way off the mark. I had envisaged

Nepal to be a tiny, mountain-locked country, sparsely populated by friendly,

homogeneously Tibetan, buddhist citizens concentrated in Kathmandu. Well...I

got the friendly part right. Otherwise, Nepal's geography ranges from

the Top of the World all the way down to tropical jungle. The 25 million+

Nepalis are overwhelmingly Hindu (>90%), live mostly in rural villages

and are segregated into ethnic regions that are stultifyingly different in

their appearance and customs. Nepalis always guess wrong in trying

to guess my origin, probably because they themselves are so ethnically diverse

that anybody from eastern, central or southern Asia could pass for a Nepali.

I think they just don't realize this. I am assumed to be Nepali, which

turned out to be very beneficial in cities where foreigners are charged a

relatively hefty entrance fee to enter certain touristic zones. If

I keep my mouth shut, keep my camera in my bag and walk purposely, then I

am Nepali. Never did I have this cover of anonymity in India. I

was told again and again by local people that they thought I was a Nepali

at first.

Seeing Nepal and India back to back underlined the stark contrasts between

the nations. Nepal is much cleaner and tidier than India. I saw

shopkeepers cleaning the streets in front of their stores, something I never

saw in India. There are very few hustlers or touts in Nepal. Nepali

merchants adapt their products and services to the needs and wants of their

clients, which was almost never the case in India. Nepali kids actually

smile and don't grow up learning a contempt for foreigners, which is the

impression one gets in India. Nepalis are diffident and respect personal

privacy and space. When they do open up from their reserved shell,

I found them to be sincere and honest. Conversely, personal space

doesn't exist in India, where you are fair game to be grabbed, cajoled, sneered

at, pushed out of the way, or cheated. It seems clear why travellers

feel more comfortable in Nepal. But why are these countries so different

in so many ways? They share a religion, an Indian-dominated mass-media,

and poverty problems, and there is no geographical barrier between India

and Nepal along most of their shared border, like there is between Nepal

and Tibet (in the form of the Great Himalayan mountain range). Nepal

was closed to the outside world by the British forces for centuries, but effectively

so was much of India. It's still a conundrum to me and hopefully someone

can share some insight with me.

There is no railway in Nepal and all transportation in the country flows

through essentially two principal east-west highways, linked by a critical

connector highway in abyssymal condition. The state of repair of buses

is considerably poorer than in India and the roads are comparable to the

worst roads in India (and I say that having ridden once in an Indian bus

that hit a pothole and flung me vertically 40 cm into the air, slamming my

head onto the steel overhead luggage rack). Some tourists seem to get

the impression that Nepal is wealthier than India, which I think is because

Nepalis are cleaner, calmer and don't act desperately or get in your face.

It is also the case that the commercial Nepalis that one encounters

in tourist towns are much better off than the countryside peasants who never

see tourists. But it is a country that does indeed have desperate needs.

One newspaper article I read described a shift of some professional

working people into vegetable farming because it was fast becoming a more

lucrative career path.

The political stalemate between the apathetic, megalomaniac King (labelled

a modern day central Asian Nero by some), corrupt and bickering political

parties that never did anything to earn the public's trust when they had

power, and the brutishly violent and dogmatic Maoist rebellion, has tuned

out the average Nepali, who is stuck between a rock, a hard place and an

even harder place. It is a hopeless lose-lose-lose situation and there

doesn't appear to be any promising prospects for improvement in the near

future. One respected Nepali international diplomat has voiced fears

that the nation is on the verge of collapsing into a failed state, with eerie

parallels to Cambodia in 1975, where a radically indoctrinated military managed

to usurp control of a peace-loving kingdom from an impotent and ineffectual

quasi-democratic central government, leading to indescribable horrors. On

the ground, these problems hardly affect the tourist at all, and Nepalis

of all persuasions are very careful about protecting tourism, as it is the

second largest source of income in the country after foreign aid. They

are grateful to have tourists, and fight their civil war behind velvet drapes

shielding tourists from the fear and uncertainty in their hearts.

No tourist has been killed during the many years of low-level conflict. Maoists

are known to collect an arbitrary "donation" from tourists on popular trekking

trails that they control, but they hadn't been seen on the trails that I

took for several weeks. Government military roadblocks stop all buses

along key points of highways and at entrances to cities, to search for Maoists

and their arms caches. This tends to delay transit times considerably

but cause no further inconvenience. Rock throwing confrontations between

protesters and government troops occur frequently and regularly in Kathmandu,

but never in the tourist districts of Thamel or Durbar Square. To

many tourists, Nepal appears to be a peaceful, happy, friendly Asian alpine

paradise; and that's how Nepalis would like you to see it.

PART 5: YAK YAK YETI

The spring trekking season in the Annapurna region peaks in March and

by late April, the rainy season approaches and visibility tends to diminish,

so I made trekking my first priority in Nepal upon arrival in the 2nd week

of April. The western hub city of Pokhara is second only to Kathmandu

in tourist traffic, and I found the Lakeside tourist ghetto to be surprisingly

clean and modern and completely adapted to western tourists. All signs

are in English and everybody speaks good English, even better than in Indian

tourist cities though Nepal was never a British colony. Before entering

Nepal, I had some concerns about the availability of merchandise in the

country, but a quick glance up and down the main street quickly dispelled

that fear. Plentiful restaurants served up all manner of creative

dishes designed to imitate those from the tourists' native countries, and

some of these concoctions are more successful than others. Still,

they try hard to please and industriously make do with less than optimal

supplies. Though it is a comfortable place to kick back, Pokhara itself

is not a primary attraction. On clear days, the 7000m high mountainscape

of the Annapurna range is clearly visible from town, and beckons to hikers.

I had originally arrived in Pokhara intending to find other trekkers or

at least join up with a trekking group organized by a local agency to save

on the costs of a guide. After a couple of days of footwork, I soon

realized that this would be a difficult task because the peak time of the

spring trekking season had past and relatively few trekkers were in town,

and the few that were didn't want to do the Annapurna Sanctuary Trek, which

I had my heart set on. Unlike the more famous Annapurna Circuit trail which

goes around the Annapurna range, this trail leads straight up into the womb

of the Annapurna peaks, culminating in the Annapurna Base Camp (ABC) at 4100m

(13,500 ft). In a fairly short time, you get both the village life that

has made the Circuit so popular, combined with the in-your-face Himalayan

scenery that draw trekkers to the Everest Base Camp trail. So not finding

any suitable groups for the Annapurna Sanctuary and not wanting to linger

any longer in Pokhara, I set out alone with no guide and no porter. Pokhara

natives assured me that there were no safety issues, the trails were well

marked, and that there were always plenty of trekkers on the trail on any

given day. All of this turned out to be quite true. Each day I joined

up with one of many different groups and got to meet just about everybody

along the route. The advantage of this method was that I was free

to go at my own pace, make detours or stops as desired, choose my own lodges,

and not have any set timetable.

On day 2 of the ascent, I veered off on a wrong trail thanks to not having

a guide, and found myself in the middle of what turned out to be a Nepali

New Year's (April 13 this year) party in a village gathering place not far

from Chomrong. The villagers warmly welcomed me to join them, which

I did for a few hours. They offered me tea and soft drinks and eventually

even sat me down at the table of village elders and leaders at the back

of the makeshift party tent, with the best view of the Nepali dancers that

later took the stage. A couple of the villagers spoke English and

cordially chatted with me, but overall, the trademark Nepali privacy prevailed

and I was left to savour the atmosphere of the festivities as an invisible

outside observer. The open warmth of their reception, without any

pretense nor attempt to benefit from me, invigorated me and gave me a wonderful

first impression of Nepali life. That a backpacking foreigner could

be seamlessly slipped into an intimate local gathering, off of the main trekking

route, without even the slightest hint of disruption is the most compelling

testament to Nepali culture (or at least ethnic Gurung culture) that I could

cite.

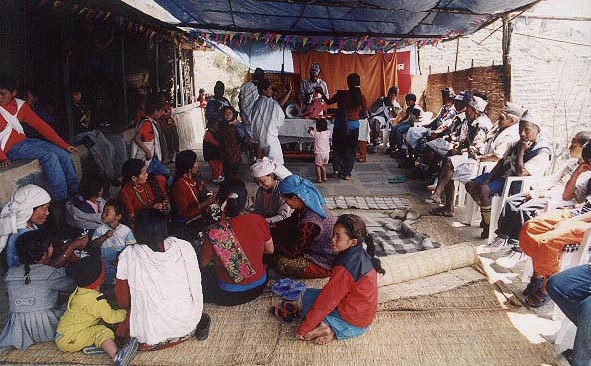

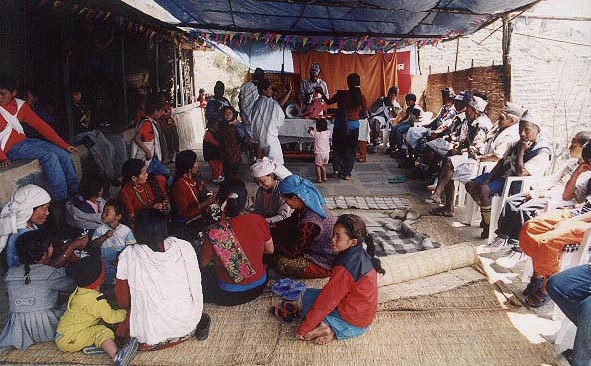

The party tent of the Taolu village New Year's party comprised

of a circle of women weaving flower garlands for the evening festivities,

onlookers seated on the side, and the table of village elders at the back

of the hall.

Taolu villagers model the latest in Nepali traditional costumes

After the first couple of days of climbing the steep ups and downs of Nepali

trails, your legs and lungs start to get used to the routine, and so I found

the last two days of the 4 day ascent up to ABC quite a bit easier than

the first two days, though more elevation is gained and the air is thinner.

Altitude problems didn't seem to affect any trekker that I had met,

though one fellow suffered mightily from a parasite infection in his gut.

On day three, we were pelted by a vicious hailstorm the likes of which

I had never seen. A torrent of almost grape sized stones accumulated

quickly and blanketed the ground with a 5 cm deep white layer in a matter

of 20 minutes. The rest of the day proved to be a cold and wet experience,

as I didn't have the time or foresight to waterproof my hiking shoes before

starting the trek. From that day forward, precipitation would fall

every afternoon starting around 2 pm in the afternoon, though mornings were

usually clear and sunny. An early start to the day helps considerably

in covering ground. On the last day of the ascent, we arrived

in the Annapurna Sanctuary, a pocket enclosed 360° around by the snowy

peaks of the Annapurna. It is a breathtaking gem of alpine panoramic

scenery that held each and every trekker in its enthrall.

The Machhapuchhare (FishTail) mountain is the smallest of the great

Annapurna peaks at just a shade under 7000m, but its distinctive, aesthetic

form and its proximity to the trekking trail and to Pokhara confer an allure

and legend that is unsurpassed. As viewed from the Machhapuchhare

Base Camp inside the Annapurna Sanctuary.

Shortly after we arrived at the ABC around noon, a thick whiteout cloud

rolled into the camp, but we learned from those who had stayed the previous

night at the camp that there had been no visibility at dawn either, and so

they decided to stick it out another night. Life inside the lodges is

convivial and social, with trekkers, guides, porters, and staff all mingling

around a large heated table in the dining room. In the near freezing

temperatures, few choose to stay in their unheated rooms, and so every night

is a little party in the dining room. The food at all of the lodges

along the trail was surprisingly tasty and as it turned out later, better

than what was served at tourist restaurants in Kathmandu, in my opinion. Or

maybe it just feels that way after a few hours of trekking! And the

meals are inexpensive considering that all supplies are carried from 2000m

up to 4000m by human porters after the last mule-accessible village of Chomrong.

I slept restlessly that night, perhaps in part due to altitude adjustments

and perhaps in part from excited anticipation. I woke up without the

help of an alarm at 5:15 am, when the darkness of the night beats its initial

retreat, and I stumbled outside into the crisp subfreezing predawn air.

Many others were already positioned on the viewing ridge waiting for

the sunrise, and nobody made a noise. The absolute cold, eerie stillness

of the ABC is a palpable feeling that one cannot forget. The last time

I had this feeling was over ten years ago in Montreal, when I went out in

the middle of the night in -20°C temperatures to play ice hockey

with friends on an outdoor rink and other pickup players joined in through

the night. The first dawn ray strikes the top of the Annapurna I peak,

one of the small handful of 8000m peaks in the world, lighting the tip with

an orange glow that slowly descended down its great massif. A few minutes

later, the first direct rays break out over the eastern peaks, illuminating

the Base Camp. This dawn ritual delivered by the Himalayan heavens

was one of the most awesome moments of natural beauty I have ever experienced.

In an ambitious manoeuvre to maximize my touring time in Nepal, I flashed

back down the trail and returned to Pokhara in two days, to complete the

trek in 6 days total. Most agencies advertise the Sanctuary trek as

an 8 to 10 day trek. My knees and thighs weren't very happy about my

strategy, but I did make it down without injury and was able to depart Pokhara

the following morning and move on to my next destination to recover and relax.

The first dawn rays break out over the eastern ridge, looming over

the Annapurna Base Camp.

Standing at the Nepali prayer flags, commemorating the mountaineers

who died climbing the 8000m Annapurna I peak, pictured in the centre above

the stupa.

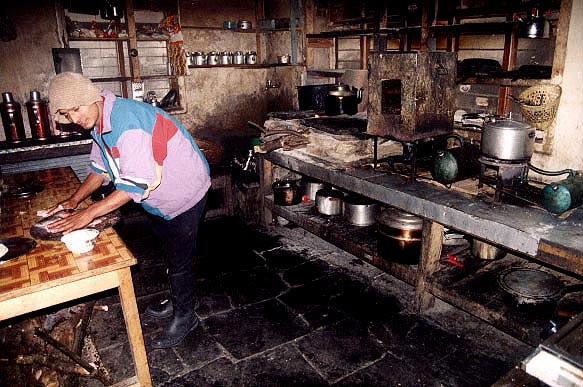

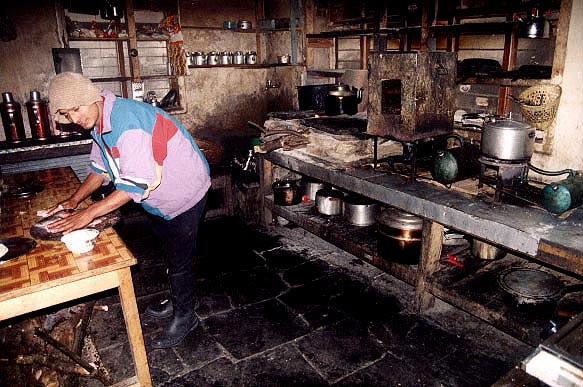

The cook at the Annapurna Sanctuary Lodge whips up dinner in the

lodge kitchen. Kerosene is the only energy source in the higher reaches

of the Annapurna trekking region.

BACK: PART 4 FEELING SIKH AND

BHANGED UP

NEXT: PART 6 KATHMANDU, NOT CONSTANTINOPLE