PART 2: VERY FENI

After spending a couple of days in Kochi to recover from exhaustion, it was time to head north on an overnight train to Goa, the Portuguese colony ceded to India by force in 1961. I didn't have the time or desire to head out to the legendarily decadent Goan beaches and the stultifying humidity had already chased out the majority of tourists. Certainly in the capital city of Panjim (Panaji in Portuguese) where I stayed, I did not frequently come across other tourists. There were no others in my cheap hotel, where I discovered the joys of bedbugs for the first time in my life. The annexed state still retains much of its colonial character, perhaps not so much in its buildings (where Macau for example looks much more Portuguese) but in its culture and the disposition of its residents. Goans are a friendly and sociable bunch and it was much easier to strike up conversations and talk about what people there really think than in other parts of India. Everybody speaks excellent English, the best in India perhaps due to the heavy tourism, and most older generation Goan catholics still speak Portuguese. In neighbourhood back alleys, English was often heard as a lingua franca between Goans that may prefer it to Hindi, which is hardly spoken here. Konkani is the traditional regional language but there are many trnasplanted Indians who have moved into Goa from other regions.

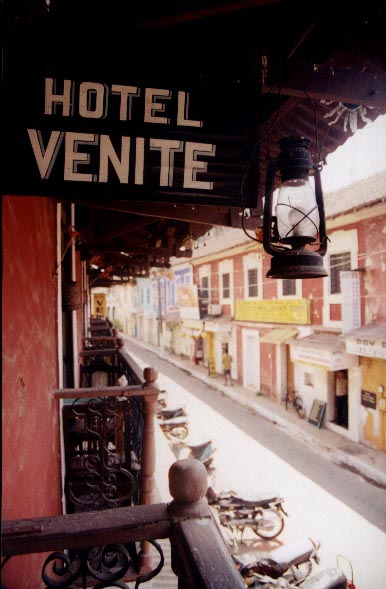

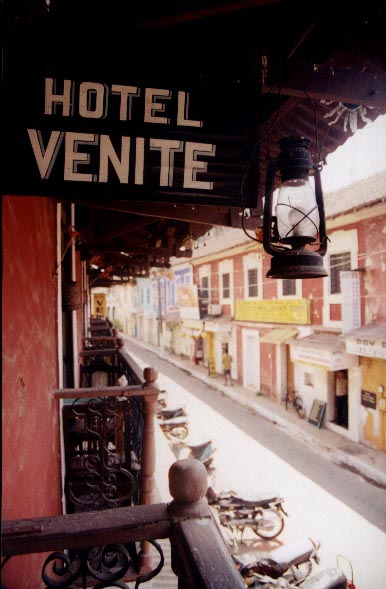

From the balcony of the rustic Hotel Venite restaurant in the old Sao Tome quarter of Panjim, Goa.

The residential neighbourhoods of Sao Tome and Fontainhas west of central Panjim still exude Portuguese flavour in its architecture, pastel colours and establishments. Some of the best meals I enjoyed in this trip took place in the back alleys of Fontainhas. The seductive combination of fresh fish from the Arabian sea, Portuguese seafood cuisine and Indian spices left a lasting favourable impression on my taste buds. The relative lack of hassle in Goa compared to most of India, whether due to cultural differences or to higher living standards, tends to put one at ease walking through the quiet, atmospheric streets and alleys. Though maintenance is poor, and indeed condemned buildings are not difficult to spot, it does indeed still feel like a tropical colony in these older, less touristed neighbourhoods

Certainly Panjim tries to take advantage of its Portuguese heritage to

draw in tourists. The best preserved colonial buildings in the city

centre were recently renovated or restored, and now house the India tourism

office and the judicial courts. The rest of the city centre, however,

consists of a more ramshackle Indian style of contemporary design. While

walking through the city centre one evening, I saw large crowds of people

congregating on the far end of the central plaza and walked over to see what

was happening. It turned out that I had stumbled onto the annual parade

for Holi, the nationwide weeklong Hindu festival celebrating the end of

winter. Though Holi had been taking place throughout my time in India,

by the time I reached Goa it had slipped my mind because locals weren't

painting their faces and bodies purple like in other places. The bright

colours of the parade floats quickly compensated for that. Marchers

and motorized floats carrying all manner of religious Hindu gods and beasts,

from the cuddly to the terrifying, gracefully floated their way down the

main commercial avenue of Panjim. One float sporting a large red demonic beast

wielding a battleaxe swung wildly from side to side, his axe not missing streetside

spectators by very much at all! I was fortunate to hit such a major

festival parade after getting blown away by the Carnaval in Las Tablas, Panama

just two weeks before. Locals on the street of course assured me that

this Holi festival was nowhere near as elaborate as their own raucous Carnaval,

so perhaps I'll never know.

Scenes from the Holi festival parade in Panjim, Goa, replete with action floats and special effects. Note the gust of smoke blowing out of the mouth of the figure on the left.

After the last float zipped by, I started walking in the direction of

my hotel, but in search of feni, a liquor distilled from the cashew plant

uniquely in the Portuguese colonies of India. I was going to leave

Goa the next day, so I figured I had to find it that night. I popped

in and out of a few bars and restaurants and the realization dawned on me

that it was going to take a bit of luck. The liquor stores had closed,

and establishments were not permitted to serve alcohol that weekend, because

of local elections taking place. I didn't have much hope of finding

cashew feni until I slipped into a back-alley bar near the central plaza.

When I stepped in and asked for a cashew feni, the smiling proprietor

naturally explained that he was not legally allowed to serve alcohol that

weekend. But before I could nod my brief thanks and step back out into

the night, he continued, "But I can serve you a Coke," with a twinkle

in his eye. He brought out a bottle of Coke from the refrigerator and

told me to take a few sips from the bottle. Then he took back the bottle,

and out of sight behind the bar, he fiddled around with the bottle. When

he came back up and handed it to me, the liquid level was replenished to the

original height. I was told to invert the bottle of couple of times,

and the mixing induced some heavy bubbling. Well, it didn't taste exactly

like Coke, but it was good! There is indeed a pleasant cashew

flavour and the harshness of the brew was taken away by the soda. I

sat down with a couple of the bar regulars and chatted for quite a while.

The surprisingly westernized clients, who had grown up around the time

of Goa's annexation, freely talked about this, that and everything. The

fellow I spent the most time with spoke English, Portuguese, Konkani and Hindi,

couldn't stand Bollywood movies (the bar TV was showing Mission Impossible

on a cable channel), and confessed with Goans love their drinks. Indeed,

alcohol is exponentially more widely available and cheaper in Goa than anywhere

in India, where alcoholic drinks cost first world prices. The feni &

Coke I enjoyed cost only slightly more than the Coke itself, and I went on

to enjoy a second one, followed by a cruder feni mixed with Limca, a lemon-lime

soda. I regretted later on not buying a bottle of cashew feni in Panjim

to take to other parts of India and share with other travellers.

The next morning I hopped on a bus to the nearby historical town of Old

Goa, formerly the ancient Portuguese capital city. There's not much

left now except for a bus stop on the highway and the remnants of Goan churches

and a few tourist shops and restaurants. The cathedral and churches

are quite impressive, even by European standards, and well preserved. The

state of Goa does a good job in the conservation of historical sites and

buildings. Of interest to Catholics, one of the churches, the Bom Jesus,

contains the remains of the roaming missionary Saint Francis-Xavier which

are opened for public viewing once every ten years.

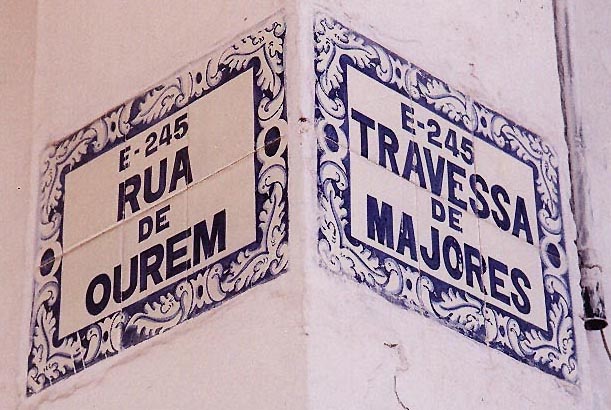

A Portuguese street corner sign in the old Fontainhas quarter of Panjim, Goa.

The overnight train headed for Bombay came almost two hours late, but

by the time we arrived in the Bombay area, it had almost completely made

up the lost time. While I was happy that I was able to make my anticipated

connection, it sure makes you wonder how much buffer time they tack on to

train scheduling and how slow these trains really are (I figured most ordinary

long haul trains average 40 to 50 km/h). While aboard this train, I

studied my guide book and Trains at a Glance and decided to forego Bombay

and instead proceed onto archaeological sites more inland in the Maharashtra

state. Bombay is undoubtedly the most cosmopolitan and dynamic Indian

city, but also the most expensive, and I was still focused on time constraints.

I had a very tight connection to make at the Dadar rail station near Bombay,

with about five minutes to get out of one train, find the ticket office,

buy an onward ticket and then find the connecting train. An extraordinarily

annoying tout met me on the platform and was actively hindering my quest

to find the ticket office before I finally had to raise my arm as if to strike

him before he scurried away. But I did succeed, with the help of other

Indians in the ticket queue, and just made my train to Aurangabad by mere

seconds.

I was not certain about my decision to spend the time in visiting the prehistoric

Ellora and Ajanta caves, until I went there. It turned to be probably

the best routing decision I made on this trip. The nearby base towns

of Aurangabad and Jalgaon are unassuming small towns not accustomed to seeing

hordes of tourists, reflected in the paucity of touts and lack of spoken

and written English. The coolness of the dry, elevated plateau was

a Godsend after enduring the sweltering coastal humidity in Kerala and Goa.

It wouldn't have been a bad region to hang out for a little while, but

I was there for the caves, both of them anointed UNESCO world heritage sites.

I had never heard of Ellora and Ajanta before arriving in India, and

I am still puzzled why they aren't cited in the same breath as Petra in Jordan.

Both are exquisite systems of caves and temples carved onto cliff faces.

Petra is larger and vaster, but Ellora and Ajanta have much more impressive

scuptural and detail work.

The centrepiece of the Ellora Caves is the awesome Kailasa temple, an immense

Hindu shrine chiseled out of the rock escarpment. No words or pictures

can sufficiently convey the awesome magnitude of this place as you walk in.

It is the largest stone monolith in the world, but every square centimetre

is lathered with fine detail, even in deep dark corners and in places where

nobody would see. From the floor of the temple, you can't see the top

of the temple. From the adjacent rock paths overlooking the temple, tourists

walking along at ground level appear about as nondescript as ants. If

forced to name the single most impressive manmade structure that I saw in

South Asia, I would not hesitate to cite the Kailasa Temple. The Ellora

cave system also comprises 33 other carved caves which include Hindu, Jain

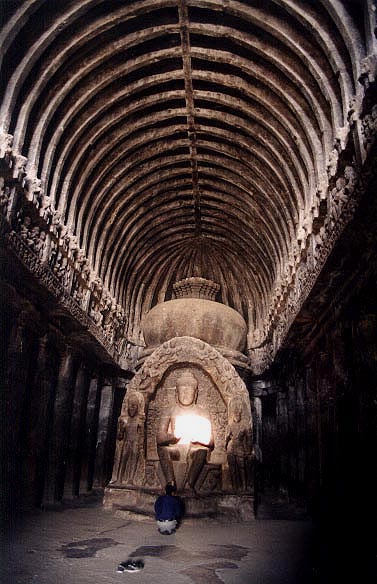

and Buddhist temples. Most impressive of these are the Buddhist chaitya

style temple caves, ribbed along its ceiling as if they were wooden support

beams.

Overhead view above and behind the Kailasa Temple of the Ellora

caves, carved out of the surrounding rock as one immense monolith. Even

the 24mm wide angle lens that I used here was not quite able to capture the

stultifying dimensions of this marvel.

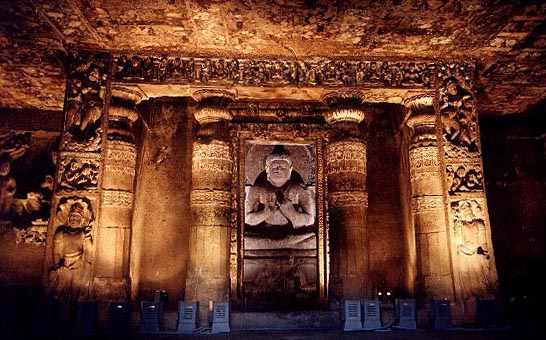

A worshipper kneels in front of the Buddha, illuminated through

a carved window, in the chaitya temple in cave 32 at Ellora. Remember,

this is all carved out of a single rock!