Myanmar: Behind

the Bamboo Curtain

The first

question friends who know anything about Myanmar (Burma) ask me is: so whatís it like -- is

it really a backward, anti-utopian, basket

case country run by loonies enslaving locals?

When put this way, the answer is no. The

infrastructure is excellent, better than Laos and most

countries that have similar GDPs on paper.

The people are friendly, work hard most of the time, get along

with each

other very well within their community and get along normally with

their local

authorities. The money is in sane

denominations, no longer the 15, 35 and 90 Kyat notes imposed by former

dictator/numerologist Ne Win.

Life goes on as youíd expect to see anywhere

else in the region. There is indeed fear

of the regime and repression, as in other oppressive dictatorships. I witnessed traffic police harshly treating

traffic offenders, and I myself was confronted by an angry soldier who

thought

I was taking pictures of the bridge we were standing on. People

are very careful about discussion of

politics on the street, but they do, and are quite happy to talk about

it with

strangers, which surprised me.

Probably

the most serious human rights abuse accusation leveled at the ruling

military

junta is enslaving youth populations to do hard labour

work. While I have no doubt that this

does still occur, especially in the countryside and in

tourist-forbidden zones

of Myanmar, I did not personally see evidence of this.

It is fashionable to point out that the

digging of the moat around Mandalay palace was done by enslaved

residents. But another version this story

that Iíve

heard is that locals were forced to work one day a month, not unlike

obligatory

military service in other countries. So

how draconian is the regime, and how much of this is hyperbole? I donít know.

Burmese script on a monument

in Mahabandoola Garden in Yangon, with the Sule Pagoda in the

background.

I met

more or less free people that could do what they wanted, as long as

they obeyed

the highly corrupt and self serving authorities, of course. All Myanmar people insist that their country

is rich with resources, the richest in southeast

Asia. It is the regime that has bled off

the wealth of the nation, leaving little for the common citizen. But there are private citizens with quite a

bit of money, enough to buy cars and property.

Some of them undoubtedly have military connections.

One way the regime rewards soldiers is to

sell them precious gasoline rations at below-cost official prices (180 Kyats/gallon), which they resell on the black

market for

higher-than-free-market prices (over 2200 Kyats/gallon,

or $2.50/gallon). Many of the

wealthy

have worked abroad and brought back money to start businesses. You need money to do this of course. A work permit for South Korea costs 2.5

million kyats ($27000) in fees and bribes,

but 2 or 3

years of income could easily yield a healthy financial return upon

return home.

The major

roads are paved and in excellent condition.

There are street lights along stretches of main highways. Almost all buses are secondhand Japanese

models. The more modern buses running

the fiercely competitive Yangon-Mandalay line are

all

air conditioned with DVD video systems.

Hotels are in excellent condition, as in fact were most of the

buildings, which surprised me greatly. I

couldnít believe they had strong hot water and powerfully flushing

toilets,

plumbing that England for example could learn from.

A

new rail and road bridge between Mawlamyaing

and Mottama, which had to be at least 4 km

long, was a thing of

beauty. One local told me that all

this

is just a beautiful faÁade that the government has built to impress

visitors

(such as those currently attending this year's ASEAN conference hosted

in the

capital city of Yangon, formerly known as Rangoon).

But after over two weeks of poking around the

country, including to some slightly out of the way towns, I have

come to

believe that the infrastructure is in fact pretty good in Myanmar, much

better

than I expected. Other travelers I met

all agreed. I can't explain why that is so, but the lack of

destruction wrought by civil war, as was the case in Indochina,

probably helped. So whatever the

motivations

for the government are, these public service projects are helping the

people

and commerce as a whole. And commerce

does go on. Markets are as lively as

anywhere else in the region, and there is no shortage of goods. Good food is copious, diverse and affordable

to all, unlike in Cuba for example.

I donít

want to give you the wrong impression, though.

Daily living standards in Myanmar is

very low. All cooking is done by burning

charcoal,

purchased for 700 Ky

($0.75)

per giant bag. Natural gas stoves are

unheard of, because of course the vast natural gas reserves of the

country are

being piped into Thailand and fattening the cats of the Myanmar regime. Most people live hand to mouth from day to

day. This is perhaps best illustrated by

profiles of individuals:

My

trishaw (bicycle rickshaw) driver who delivered me from the Mandalay

bus

terminal to the city was a cheery chap who spoke good English. Many people are learning English themselves

from a book

as

a way to tap into the tourist money, which tells you how important a role tourists have come to play in local

economies. The asking price was 1500 kyats

($1.70), which Iím sure included a hefty foreigner premium, but was

fair enough

if he was going to cycle me and my backpack 10 km.

In fact, the central bus terminal of Yangon

is an even more ridiculous 27 km from the city, which is apparently for

government corruption reasons. He told

me he was very happy to have a customer that morning.

Some days he has no customers at all. With

the 1500 kyats

I paid him, he could feed himself and the owner of the bicycle. On a lucky day, he might have a second

customer in the afternoon. With those

additional 1500 kyats he could feed his

parents and

put money aside to pay the annual 7000 kyat licensing fee for operating

a

trishaw.

My

trishaw driver in Bago who took me around

to the

major sites in 2 hrs early one morning spoke excellent English. His 50-odd years made him less robust on the

bicycle than the Mandalay trishaw driver.

Clearly educated, I wondered why he was operating trishaws for

tourists. It turned out he was a primary

school teacher

who had to teach English among other subjects to his students. He quit 9 years ago because the state paid him

1500 kyats ($1.70) per MONTH, and that was

not enough

to feed his family. Apparently salaries

have since risen to 9500 kyats ($11) per

month, but

that is still well below the poverty line.

He once met a Thai primary school teacher who makes $100 month

typically,

with comparable expenses in Thailand as in Myanmar, and envied that

salary,

which would have allowed him to live very well indeed in Myanmar. I handed him the 1500 kyats

asking price for the tour and he appeared very happy with it.

I met 23

year old H.M on Mandalay Hill, a common place for eager students to

intercept

English speaking foreigners to practice conversation.

I later met him for tea at the home of U.T.W.

an older ruby trader who couldnít find work and is now perfecting his

English

to hopefully work in tourism one day.

U.T.W. is a de facto

mentor of many of the younger eager

students of the

Mandalay Hill club. H.M.ís

story was a poignant one. Impoverished

from a countryside family, he moved to Mandalay to learn English in

order to

find a way to make money. Staying at his

auntís home, he bicycles an hour everyday into Mandalay city to attend

English

classes at a monastery. 15 hours a week

of group instruction led by a monk, that

costs 1000 kyats ($1.10) per month, cheap

even by Myanmar standards. I attended one

of his classes, and students

were enthusiastic about speaking English with a visiting native speaker. Because of the tourist boycott, it is not

easy to land an American. On weekends,

he hits Mandalay hill to practice with foreigners.

Though not the most gifted student of

English, he is very motivated. When I

invited them to join me in visiting the temple hill of nearby Sagaing, H.M. declined.

I asked why. Because he couldnít

afford the 200 kyat ($0.25) bus fare, which of course I then paid for

him. We discussed his ambitions.

He asked me to send an email off for him, to

an Israeli army major that he had befriended some months back. The Israeli had promised to spring H.M. out of

Myanmar. I asked him how he was going to

get out of the country. He didnít know

but he reckoned he could walk into China and then into Thailand, where

the

Israeli could pay his airfare out to Tel Aviv and help him find a job. That was his plan, anyway.

I warned H.M. that it wasnít going to be this

easy, especially as he would be a purely economic refugee, but H.M.

didnít want

to hear that. He was going to do

whatever it takes to get out. I

sincerely hope he doesnít meet bitter disillusionment.

Such a nice, sincere, earnest fellow,

and probably not an atypical case in Myanmar.

Should I

Stay or Should I Go?

Among travellers, there is probably more discussion of

morality

concerning Myanmar than surrounding any other country.

Should one boycott travel there? Should

there be an economic embargo? The

moralizing seems to outweigh the actual

body of firsthand information coming out of the country.

If there is one clear reason for going to

visit yourself, it's to tell others about

what Myanmar

is like. All of Myanmar, its people, its

places, its culture, and not just the military junta and its most

famous Nobel

laureate dissident under house arrest.

Granted, the typical tourist is afforded only a few weeks of

observations, but it's a lot more than what the rest of the world knows

about

Myanmar, which is shockingly little.

Remember that before Burma reopened to tourists in 1993,

outsiders had

barely even heard about, much less cared about the country. It was this reopening, economically as well

as to tourism, that ignited the current

international

debate and interest there. And that's a

good thing in every way.

Those who

understand me well realize how much I despise political correctness and

cults

of personality. For me it's all about the people, and what's best for

them in

the long run. Some of the most

experienced and interesting travellers

I've met on

the road have also share this curious apolitical stance toward such

entrenched

issues. Call it moral relativism if you

will, but I'm not seeking to create any Darth Vaders

or Jesus Christs here.

The main

reason for calling to boycott tourism in Myanmar is, as far as I can

see,

because Aung San Suu

Kyi and her National League for Democracy

party have called

for it, in order to deprive the ruling junta of this foreign income

source and

to ostracize them under the glare of the international eye. Aung San is

the

daughter of the martyred father of modern, independent Myanmar,

assassinated by

rivals shortly before formal liberation from the British empire. She has

since valiantly opposed the military

dictatorships and repression that has beset her homeland for the last

half

century, and I admire her courage and stubbornness.

One has to have both to win that

fight. And she has the people's support

as well. She won the 1990 election that

was annulled by the ruling junta. Those

Myanmar citizens I've talked with (behind closed doors of course) see

her as

their shining hope and inspiration. And

how can one put a price on inspiration?

One man in his 50s, who's seen the whole run of bad times, calls

her

"My Lady" with a twinkle in his eye, and I knew to whom he was

referring. When I hear Aung San mentioned in public by tourists, the

usual reactions

you get from locals are either a vociferous downplaying of her out of

fear of

being drawn into that dangerous discussion ("their spies are

everywhere" I heard on many occasions), or else silence with that same

twinkle in the eye. Every great revolution

and liberation from tyranny needs its heroes, and Aung

San fits the bill impeccably. How she

fares as national leader afterwards of course is a different story, and

one

that is too far away on the horizon to seriously contemplate now. I'm not much into idolatry and remarkably

similar stories involving Benazhir Bhutto,

Indira Gandhi, Corazon Aquino

and

Megawati Sukarnoputri do not portend well. In

any case, the coming of such a transition phase is inevitable,

necessary, and

very welcome.

Many

other notable anti-government dissidents, who also admire and respect Aung San, do not share her emphatic call for a

boycott on

tourism. They view this as an unfair

punishment on the impoverished people, who would be denied the

opportunity to

make a dollar or two from tourists, for an idealistic and thus far

phantom goal

that has eluded generations of ordinary Myanmar people.

Is she selfish to use her clout to press for

a heroic overthrow of the brutal regime, at the expense of the

suffering of her

people? Is she the queen born with a

silver spoon in her mouth, who has never known what it is like to

suffer in

abject poverty with no hope or chance to advance one's

owns modest desires and needs? Does she

hate the regime so much that she's basing her decisions based on hate

rather

than love? Of course, I can't even

pretend to have any informed thoughts on these rhetorical questions. I was just a tourist for 18 days who hasn't

even read her writings, but I just like to consider both sides of any

debate. I never did like the concept of

political debating, where it seemed that you had to be all white or all

black in

order to play the game correctly. It's

just not me.

The real

question is: does the tourist money directly help the junta repress its

people? My conclusion is no, backpacker

spending is a drop in the bucket, and will affect the people positively

overwhelmingly more than negatively.

Package tourists spend a lot more money, and more of their money

goes

directly to the government, so that involves a different equation, but

I don't

know the numbers on that. OK, letís look

at the money. It used to be that travellers arriving in Yangon airport (until

recently, the

only legal point of entry for tourists) were obliged to exchange

US$250, 200,

or 100 for Foreign Exchange Certificates (FECs),

dollar-equivalent notes that had no value outside of Myanmar. FECs were not reexchangeable for hard currency upon exit from

Myanmar,

and thus your money stays in the country.

The government then would exchange these FECs

for local Kyats at an artificial rate

about a hundred

times worse for you than the black market rate.

They would thus pocket 99% of your money, unless you knew to

seek out

the black market. This FEC system is now

abolished, and there is no pressure on visitors to exchange dollars at

official

rates (which still suck). It is easy to

exchange money on the black market in any town, and this even appears

endorsed

by the government. So we've come a long

way in a decade. Today's backpacker

sporting the new FIT (Foreign Independent Traveller)

visa can spend their money any way they wish.

They can avoid spending the money directly on government

companies and

institutions if and when they choose.

Some idealists go out of their way to avoid any such spending,

and I

respect their choice. I would say I'm a

typical backpacker as far as government spending goes.

Let's break it down:

$25

Myanmar visa in Bangkok

$10 Bagan

entry fee

$5 Shwedagon

Pagoda entry fee

$5 Sagaing/Mingun

tourist boat and entry fee

$6 Kyaiktiyo

golden rock entry fee

$3 Inle

Lake entry fee

$3 Shwe

U Min cave pagoda entry fee

$10

international airport departure tax

So I

spent a gross total of $67 directly to the government.

That's of course not taking into account real

maintenance costs paid for by the government (such as at Bagan,

which is not a world heritage site and does not receive UNESCO

funding because the regime will not accept the conditions imposed by

the UN for its inscription). Some

travelers spend less money,

by not

entering certain sights or by evading entry fees (sometimes risking

arrest of a

private citizen if caught, which I do not approve of).

Some spend more, especially those taking

trains, whose inflated tourist prices go directly into government

coffers. Generally, by avoiding trains and

not buying

gems at government gem shops and not staying at government hotels

(which are

expensive and suck anyway), that minimizes how much money the

government is

taking from you. You're going to be

spending $50 minimum and most likely over $60, so that should be your

benchmark

when making your own moral decision about visiting Myanmar or not. There is also the issue

of indirect spending going to

the government, such as on transportation petrol surcharges, and hotel

head

taxes, but after talking with many owners of hotels, bus companies and

restaurants, I've concluded that the indirect contribution to the

government is

quite small. For example, the hotel head

tax is 10 kyat (about $0.01) per person per night.

Most of the inflated differential foreigner

prices, which infuriate some budget travellers

to no end, is pocketed by the private

interests and not passed on to

the government.

What do

the local people think? I didn't meet a

single one who supported the tourism boycott.

Whether they worked in the tourist industry or not, whatever

their

political views are (or are not), whether they were from places that

benefited

from tourists or not. The absence of

British commonwealth citizens and Americans

is very

noticeable, and the locals notice it too.

Curiously, this makes the demographic population of backpackers

in

Myanmar resemble the Axis: Germans,

Italians, Japanese, and Vichy French!

(That's a joke.) There is visibly

more money in the neighbourhoods that

tourists frequent, and they are bringing in

significant amounts of

cash to private business interests.

Market day at Pindaya, a

mountain village in the Shan state better known for its Shwe U Min

Pagoda, a cave containing 8000 golden Buddhas.

I estimate that there

were maybe a couple hundred backpackers in Myanmar when I was there,

which

was

toward the end of summer peak season.

Everybody goes by the same handful of transport routes and the

occupancy

rate of foreigners in intercity buses is still very low, even between

major

sites. You run into the same

tourists repeatedly. So I'll take a wild

stab in the dark and

guess that there are maybe 1,000 backpackers a year these days, though

this

number is definitely on a sharp rise.

Because of the abolition of the FEC system, word of mouth about

Myanmar

will only build up because it is the next "untouched" nation in

Southeast Asia. I'd say that Myanmar has

already inherited this mantle from Laos, and the most

touristy parts of Myanmar are already being noticeably spoiled. (Which is good for the locals don't get me

wrong -- I'm just speaking about tourist value.) So

at $60 from each backpacker, the

government makes $60,000 a year from all backpackers.

Enough for two of those Toyota Hiace

pickups that they somehow stuff 35 passengers into

(and onto and hanging onto)?

Considering

that the government is one of the biggest opium peddlers in the world,

monopolizes one of the richest teak and gem troves in the world, and

exports

petrol and natural gas to China and Thailand, a schoolchild can do the

math and

tell me how much backpacker ticket receipts are generating for the

junta. I went through this whole scenario

here

because I am often confronted by questions about whether it is "OK"

to go to Myanmar. Obviously, this is a

personal decision that everyone must make for themselves, but my point

is here,

your hard cash contribution to the government should not be the

dominant

reason. I find it really funny how

people who won't visit Myanmar for fear of enriching a repressive

government

may not entertain the slightest qualm about visiting Cuba, also a

country which

opens to tourists for the sole purpose of generating cash for the

dictatorship

(and much more cash per person than Myanmar, I might add), and which

represses

its people just as brutally, and where overall conditions of life are

far worse

than in Myanmar. It's not question of

democracy either.

There are plenty of dictatorship states that are popular

among

backpackers: Singapore, Vietnam, Nepal at this sad point in their history, Jordan,

Morocco,

and China to name a few. I have to

conclude

that the special case of Myanmar as backpacker pariah stems primarily

from the

heroine Aung San Suu

Kyi and her noble cause and has been

romantically magnified

by political correctness and righteousness and fuelled by the media.

Some

western anti-government protesters even insist on calling the nation

Burma and

not Myanmar, for the sole reason that it was the ruling regime that

made the

official name change in English in the 1990s.

It's rather petty and has nothing to do with reality. Burma was the British colonial name,

bastardized from Bamar, the name of the

dominant

ethnicity in the country. There are

however many ethnicities and cultures within the country, and hence it

is the

Union of Myanmar. Myanmar is how all

Myanmar people call their own country in their own language (or sounds

more

like "Myanma" actually), so why shouldn't

we? Regardless of who finally instituted

the change. A no brainer for me. To insist that calling the country under its

colonial name is more morally correct is a bit patronizing. Ironically, it seems to me that many of those

who refuse to acknowledge the name Myanmar are British.

The

current US-led commercial embargo against Myanmar has more serious

ramifications than pocket change from backpackers.

I am not an economist and I do not know how

this affects the economy and ruling stability of the government. It is certainly bad for the Myanmar people in

the short term. The question is whether

it will have positive long term repercussions.

My view on the current situation is that the embargo is having

little

effect on the ruling junta's grasp on power.

They have a close and powerful neighbouring

ally in China who can furnish Myanmar with anything it needs. As I mentioned, Myanmar also exports natural

gas to Thailand, and not a small amount of it.

Thailand's refusal to participate in isolating the Myanmar

regime has

led to diplomatic heat from other ASEAN nations. But

this doesn't look to change soon, and

even if it does, this is secondary to the Chinese connection. Myanmar is still selling a lot of gems to

Europe, mostly Germany, Austria and Switzerland, and the supply is

finding its

way into international markets. And

finally there's the opium money, which is rumoured

to

represent up to half of Myanmar's real gross domestic product. On a financial level, I don't think the

embargo has much hope of working in the current circumstances. Locals attribute rapidly increasing prices in

Myanmar on basic products to the embargo.

I don't know if that's true, since most of these products are

manufactured

in Thailand and China anyway, but if so, it would be an example of how

an

embargo can hurt the people without helping them in any real way, short

term or

long term.

You can't

compare Myanmar to South Africa. The

embargo had emotional consequences on Pretoria beyond the already

strict

financial ones (because they had no China to help them).

White South Africa never felt at home in

Africa, and didn't view their black neighbours

as

brothers in their shared destiny.

Rather, they looked toward their white motherland, Europe, for

support

and nourishment and even identity.

Mother Europe participated in the South African embargo,

isolating South

Africa as much emotionally as anything else.

They cared too much about being white and British for this not

to have

taken its toll. It was only a matter of time before a white leader (DeClercq) caved in.

Myanmar doesn't have this identity issue. They

have a proud independent, ancient, and

unified history, before and after colonialism.

They are Myanmar, not an offshoot of Britain, and so they cannot

be scolded

and lectured as pariah children. Only

the intellectual elite in Myanmar might possibly suffer from this sort

of psychological isolation. I don't think

anybody else

in the country,

least of all its regime, gives a hoot about world political opinion of

Myanmar. The people care mostly about

surviving from day to day these days, and trying to improve their lives.

And you

can't compare Myanmar to Iraq. Oil was the

sole source of income for Saddam Hussein's government and with

the

exception of a bit of oil trickling through a secret pipeline through Jordan and UN scandals, he didn't have many

outlets for his

product. As a result, the regime was

financially crippled and the military was ill equipped to survive the

eventual

US invasion. I'm not making political

statements here, just commenting on the relative effectiveness of the

embargos.

I am disturbed, though, that some people might have been against the

Iraqi

embargo because it was hurting the people, but at the same time for the

Myanmar

embargo despite the fact it is ineffective and also hurting the people.

The Land

of Golden Pagodas

OK,

enough of that stuff! What's there to

see in Myanmar? Plenty!

The limiting factor is normally the 28 day

visa, and not the number of interesting places in the country. It is not possible to see even all of the first rate sites in Myanmar. Everybody leaves having missed out on some of

the major destinations. The absolutely unmissable places are Bagan,

Inle Lake, and the Shwedagon

Pagoda in Yangon. Thatís what the

guidebooks say, and I agree with them.

The only

rival to Angkor in the world of ruins is Bagan.

Rather than in artistic quality and

romantic

settings, Bagan overwhelms you with the

sheer number

of pointy temples within a few square kilometers. 4

million of them by legend, 4 thousand of

them according to temple geeks, and undoubtedly not all of those have

survived

in a preserved state. Whatís left is

still enough to be mind blowing. And I

didnít count them. In 1996 I wanted to

visit one of the worldís spectacular sites, and my final choice came

down to

Angkor or Bagan. I

chose Angkor with no subsequent regrets, but

Bagan wouldnít have been a bad choice

either, especially

considering how truly special it would have been at that time to have

visited

Burma.

Bagan in the daytime as seen from the Mingalazedi pagoda (top), at sunset from near Shwesandow pagoda (middle) and detail of a door of a minor temple, Hti--lo-min-lo (bottom)

Inle Lake is a more lowkey attraction, which does

not strike acutely at your senses, but rather slowly invades them over

a day of

boating around this veritable real life Waterworld.

The entire economic and social life of the

towns and villages on the banks of and floating on Inle

lake takes place on the water, especially on its western shore, which

is

essentially half-marshy land and half-lake. It

is a seamless and intercalated maze of

waterways, canals, bridges, foothpaths,

boat landings

and wooden houses hovering over the lake surface on poles.

There

is no need nor facility for accommodating

automobiles,

and the sound of their absence is palpable. Public

and tourist transport around the lake

takes place through motorboats, but the majority of boats plying the

lake

between the villages and for fishing are still motorless.

The image of villagers poling their way

down the canal with one leg coiled around the pole for leverage is the

subject of postcards. It is

difficult for me to describe how impressive Inle

Lake

really is. The scope and breadth of the

lives of thousands of people dependent on the lake is what sets this

apart from

other floating village-type attractions in the world. Inle is not

spectacular in the usual sense of the word, but no less essential and

satisfying to visit.

ďIf You Hit the Jackpot, Eat ChineseĒ

So goes one Burmese

proverb, which I fear doesnít give enough

credit to Myanmarís own home cuisine, a distinct southeast Asian

smorgasbord of

dishes combining Indian styles with Chinese, and Thai influences. Another modern proverb spelling out a commonerís

paradise Ė Eat Chinese, marry a Japanese girl, and live in Switzerland

Ė only goes

to show what kind of cultural heterogenity exists in Myanmar after

centuries of

building and losing empires. This

confusion certainly extends into Burmese food.

I have to admit, itís one of my favourite cuisines in the area. The tempering of Thai and Indian spices with

Chinese influences, and conversely the spicing up of the dishes in the

ethnically Chinese Shan state by Indian and Indochinese influences,

creates delightfully

pleasant taste combinations. Food is

good and so are the portion sizes. One of

my

favourite restaurants was in Baganís base town of Nyaung

U. Mann

Sabai serves up their chicken curry with 11 different small vegetable

side dishes,

soup, tea, and all you can eat steamed

rice (standard practice in Myanmar). All

for an all inclusive price of 900 Kyats ($1). Delicious

biryani plates sold on city streets sell

for about 400 kyats. So if thereís one

thing travellers canít complain about in Myanmar, itís the eats. On the drink side, local brews Myanmar and

Mandalay beers werenít exactly world class, but I became addicted to

refreshing

Star Cola

(100 kyats per bottle) on hot sunny afternoons.

Searching For MíLady

On my last day in

Myanmar, I had a few hours in Yangon and

had to satisfy my curiosity about one thing.

I hopped on the all-purpose city bus #43, which links downtown

with the

two lakes, the airport, and the highway bus terminal, and costs a mere

20 kyats

($0.02). I got off at Lake Inya and

walked to the intersection of University Avenue Road, where this sign

stands:

From the map on my Letís

Go guidebook, I located where house

#54 should be, the lakeside home of Aung San Suu Kyi and where she is

kept

under permanent house arrest. Whether

she was actually there or not is a different matter, as all kinds of

rumours on

her whereabouts fly about. I

walked down the street a hundred meters or

so, and saw a traffic road barrier manned by police. As

I came within sight of them, a plainclothed

man on the street whistled to signal to someone. I

kept walking toward the barricade, where

officials inspected each passing car before allowing them to pass

through this

busy road. I

spotted a cold drinks shop only a few meters

in front of the barricade, so I decided I needed a Star Cola. I was in fact thirsty. By

the time I arrived and communicated my

thirsty ideas to the shopowners, I was surrounded by a motley crew of

uniformed

and non uniformed men. None of them said

anything but neither were they unpleasant. Of

course I was interrogated about where I was

going and innocently stated that I was interested in seeing the

University,

which was further down the road. They

told me politely that the road was not passable. When

asked why, the unique reply was ďI donít

know.Ē What were those military people

doing there? ďI donít know.Ē

What

are you doing here? ďI donít know.Ē At

that point I realized thatís all I was going to get out of anybody (the

shopowners

did not appear at ease with this discussion though they were quite

friendly to

me like most Myanmar people). So I went

on my way and visited a few more tourist sites by bus in Yangon before

retiring

at the White House hotel for my last night in Myanmar.

A

linecar is a typical public transportation vehicle in the former

British colonial capital of Mawlamyaing, though pickups are far more

common in larger cities and smaller towns.

There is so much more I

could talk about with respect to

Myanmar, but I hope this at least piqued your curiosity about one of

the most

fascinating and overlooked countries in Asia. It

was one of the most important target

countries for me on this trip and it didnít disappoint.

There is plenty enough to see on a second

trip one day, but I fear it will already by overrun by tourists by

then. The opening up of the country to

foreigners,

outside information and international commerce can only pound the wedge

deeper into

the cracks of what was once one of the most fearsomely closed nations

in the world. When you see private locals

bypassing

internet restrictions and watching live CNN and BBC world news on their

satellite dishes, you get the feeling itís only a matter of time before

they

integrate into a normal rhythm one day. Now

it certainly wonít be easy Ė take a glance at Beijing Ė but I am an

optimist,

and I left Myanmar smiling as much as their citizens smiled at me.

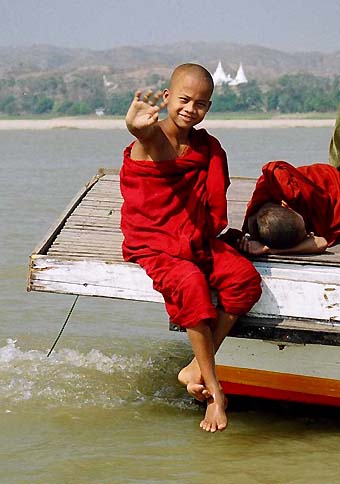

Boy monk on an Ayerawaddy

riverboat heading upstream from Mandalay.